Ektar 100 is an odd film. It’s incredibly rewarding if you use it properly, and quite close to a disaster if you don’t. Think of it as a negative film with the latitude of slide film, and it’s rewarding: depending on exposure, you can choose anything from soft, pastel colours (minimum exposure) to rich, saturated colours. Think of it as the sort of negative film that you can overexpose mercilessly, and it’s close enough to a disaster, because those rich and saturated colours turn garish and improbable, with something of a magenta or purple bias.

If you regard a good negative as a starting point, rather than as something to be printed automatically as quickly as possible, Ektar 100 offers the possibility of quality from the best 35mm cameras that can begin to rival medium format.

| This is not an unmanipulated shot — except for the colour, which is a straight scan from an exposure based on an incident light reading at ISO 100 The verticals have been made more parallel (in Adobe Photoshop) and the image has been stretched vertically to compensate for the squatness resulting from a low viewpoint and post-processing perspective ‘correction’. (Tripod-mounted Leica MP, 24mm Summilux) |

Ektar 100 is not, however, hard to use. Far from it. All it means is that you can’t do the old, lazy colour-neg trick of setting half the ISO speed on the meter. Nor, for that matter, can you use a spot meter to read an improbably dark area and rely on the long straight-line portion of the characteristic curve to record the highlights without distortion of the colours at the darker end of the subject. On the other hand, with most multi-point metering systems and anything like an average subject, or with an incident light meter, it could not be easier to use.

Bicycle Overexpose, and this is what you get: incredibly saturated colours, plus a tendency towards purple or magenta. This is on the limit of what we are willing to accept, but we quite like it, at least at a fairly small size. Otherwise, it rapidly becomes rather overwhelming. Below is a less saturated version, just to show how much you can play around with this film |  |

| Dropping the saturation by 50% in Adobe Photoshop gives a much more vintage look, as does lightening the picture somewhat (about 35% in Adobe Photoshop). You can also see that the lettering on the frame is clearer and much less blue. |

It’s incredibly fine grained: finer grained than Ektar 25 of beloved memory, despite being two stops faster. It’s very sharp, too, with extremely high resolution (the trilogy of fine grain, high resolution and maximum sharpness are not always mutually compatible). In fact, if you’re shooting 35mm colour negative, it may be the film against which all others have to be measured. Sure, there are times when you will want more speed, but that’s about the only reason we can think of to switch.

Why not shoot slide, though? Well, there’s a simple, one-word answer that more and more people will give you: processing. Kodachrome is no more, and E6 is in rapid retreat. Unless they process their slide films themselves (which is not as difficult as most people think), more and more photographers have to resort to mail order or to very long journeys in order to find an E6 lab.

Pinocchio

For bright, toy-like colours Frances took an incident light reading and rounded exposure up to the next half stop. At the incident reading, the colours would have been more muted; at +1 stop, well, you have seen the bicycle above… The trick is to round exposures up slightly for more saturated colours and down slightly for less saturated colours. (Voigtländer Bessa-T, 24/1.4 Summilux)

Possibly an even more relevant question is why you would not want to shoot digital instead. Well, there are quite a few answers here. The first is that you like the look of film. The second is that you need to shoot an awful lot of digital in order to amortize the cost of a digital camera that can give you anything like the quality you can get from a half-decent film camera and Ektar 100. The third is that you like using good old cameras: Ektar 100 in a Kodak Retina, for example, is wonderful stuff, and the camera is tiny, light and incredibly durable. In fact, it’s even a good excuse for using bad, old cameras: Ektar 100 is an excellent excuse for digging out a snapshot camera from the 1950s or 60s, or buying one from a swap meet, boot fair or charity shop. Fourth, film is a wonderful archive medium which does not need to be endlessly copied from one medium to another as electronic standards and storage media evolve.

Digital photographer It just seemed to be a nice irony, shooting a digital photographer on film… But low light (inside an arts centre converted from a twelfth-century church) meant that we needed an f/1.5 lens, and as you can see, depth of field is limited. Assuming, then, that you want to shoot colour negative film, for whatever reason, why would you use anything other than Ektar 100? As we have already said, the main reason is speed. To be sure, ISO 100 is pretty much the standard for slide films, and is a great improvement on the 64 ASA (and below) which was the norm even as late as the 1980s; but we have all been spoiled by faster films, so that today, ISO 400 is pretty much the universal speed in both black and white and colour negative films. Even so, going back to ISO 100 can remind us that an awful lot was and is possible with even a slow film like this, so unless you really need faster film for ‘available darkness’ shooting, or don’t have access to a fast lens, or both, Ektar 100 is remarkably good stuff. |  |

In fact, this leads us to another aspect of film choice. For the happy-snapper, shooting ‘a bit of everything, really’ and leaving the film in the camera for months on end, Ektar 100 may not be the best choice, but if you take a bit of care over your exposures, it really is extraordinarily versatile, the more so as you can vary colour saturation to quite an extent via exposure, just as you can with slide film, as noted in the first paragraph.

Now, we have to admit that we have not done side-by-side comparisons of the same subject using Ektar 100 and its two most obvious rivals, Portra 160 and Portra 400, but we have shot a lot of all five films (five, because the Portras are available in both NC and VC versions, Normal Colour and Vivid Colour). All five are superb, but for our purposes — scanning, followed by manipulation in Adobe Photoshop — we are reasonably convinced that we can get by very happily with just two films, Ektar 100 and Portra 400 NC, because we can control the vividness of the colour within very wide limits in Photoshop. Predictably, Ektar 100 is superb for scanning: it would be strange if a colour negative film for the 21st century were not.

Bridge and lake

Combined with the unique look of a Thambar at about f/9, Ektar 100 is capable of giving the most extraordinary richness and painterliness to a scene. This is a few hundred metres from our house, and is one of our favourite subjects, both for testing lenses and film and for its own inherent charms.

The core of the argument, then, is this: if you take a lot of time over your pictures, carefully choosing your lenses for effect, exposing carefully, or doing much in the way of electronic post-processing, then well-exposed Ektar 100 is a most excellent starting point. It is the sharpest and finest-grained colour negative film you can buy today, with admirably neutral colour (unless you overexpose by a stop or more). This is not to say that post-processing is essential. Rather, we do it because we like to fine-tune the look of our pictures.

Often, for example, we cut saturation for a nostalgic look. Modern films are far more saturated than old ones, so older photographers call them ‘over-saturated’ or ‘garish’. The truth is that even the most colourful films are rarely as vivid as the subjects they record, and that older photographers are simply conditioned to prefer less saturated pictures. Spa at St. Thomas in the Pyrenees Roger wanted the look of a 1950s snapshot, so he used a 1952 Kodak Retina IIa and guessed the exposure. The original was a little more saturated than he wanted so he simply reduced the saturation slightly in Adobe Photoshop. |  |

If on the other hand you want the very minimum of post-processing, as (for example) in wedding photography, you might well find that Portra 160 NC, generously exposed (rate it at 125 or even 100), will give you better and more consistent results across a wider range of exposures with much more of a buffer against underexposure. The pictures won’t be as sharp, and they will be more grainy, but this is rarely a major concern in wedding photography after all: in the days when Hasselblads ruled the roost, photographers often used Softar soft-focus screens to take the biting edge off the sharpness of their lenses.

| Finally, there’s price. Ektar 100 is pretty middle-of-the-road here: certainly not bargain priced, but equally, a long way from ’boutique’ pricing or silly money. It’s on the high end of average, but given its merits, this sort of price looks very like a bargain. It’s now our standard colour negative film, insofar as we use colour negative instead of Leica M digital, and if you’re serious about your photography, it may well become yours too. Building work Frances wanted to capture the faded, sun-bleached colours of the South of France, so she gave the bare minimum of exposure (1/2 stop less than the meter suggested) and then further desaturated the picture slightly in Adobe Photoshop. As with the first picture in this review, Photoshop was also used to render the verticals parallel; she used a 21/1.4 Summilux on a Voigtländer Bessa-R2. A dozen more pictures taken on Ektar 100 follow, or you may care to go back to Index/List of Modules |

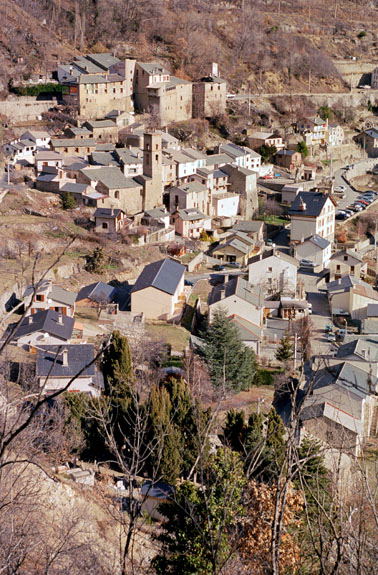

Aditi (above) Fontepedrosa (right) The picture of Aditi is to show how Ektar 100 handles very contrasty lighting (rather better than most slide films) and the picture of Fontepedrosa shows the sort of colour saturation you can expect shooting Ektar 100 at its rated speed with incident metering. (Kodak Retina IIa) |  |

Vineyard (above) and Pyrenees (below)

When we first tried Ektar 100 we often overexposed, because long experience has taught us that this normally works best with colour negative films. The result was somewhat vivid colours, as in the vineyard. When we were more used to the film, we sometimes used this vividness deliberately, overexposing the film by up to a stop, as in the picture below.

Staircase

The colours of Ektar 100 seem to us to be extraordinarily clean and clear, though of course, this is entirely subjective: the colours in a photograph are a reconstruction of the colours, using dyes, not a record of the colours themselves. Leica MP; 21/1.4 Summilux.

|  |

River Tet, Pyrenees

It was October, before the autumn rains had really started, and the landscape was blasted and dry. Overexposure by just one stop (on the right) sent the reddish-brown foliage magenta, and the grey-blue water purple.

Pipes, spa, San Tomas

San Tomas/St. Thomas is one of our favourite spas. This is one of the pictures Roger took with his Retina IIa, guessing exposures. Because he has plenty of experience, he can usually guess very accurately, but if you don’t want to use a meter, you may do well to bracket Ektar 100 until you gain more experience. This was spot-on for the degree of colour saturation he wanted.

Church, Moncontour |

Dressed lamp post, Arles |

Although we say in the body of the review that this isn’t a film for the happy-snap brigade, this does not preclude the serious photographer leaving it in his favourite happy-snap camera, whether it be an old Retina or an old Leica (two of our favourites).

Church Another view of the church at the beginning of the piece, with a bit more colour saturation. Again, verticals have been adjusted in Adobe Photoshop. |

Church Ektar 100 converts well enough to black and white, but quite honestly, we’d rather shoot ‘real’ black and white film and make wet prints. |